Ever wonder where your donated clothes end up? Using Geotags we uncover the truth behind the murky world of textile ‘recycling’ in Ireland

How many of us have dropped clothes into bring-banks or shop take-back schemes and wondered what really happened next? We assume our unwanted items will quickly find a new home nearby, naively thinking that our unwanted clothes might still be helping, not hindering. But where does that pair of jeans end up? And why is the world of textile recycling in Ireland, still so murky?

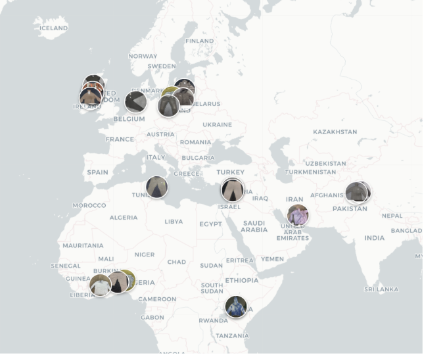

A new investigation Threads of Truth by VOICE Ireland, and the Dublin Hub of the Global Shapers aims to bring clarity to a system that has operated largely out of sight. By placing trackers in 23 donated items, the team uncovered a very different reality: 95% of the tracked clothing was exported out of the country, and 60% left the EU.

READ THE REPORT

Over a 10-month journey, these items travelled through 12 countries, including Poland, Pakistan, the UAE and Libya - revealing a complex and often opaque global trade that begins the moment we drop our clothes into a bank.

But to what fate? Despite its best efforts, VOICE was able to establish the final fate of only 48% of items.

- 30% of items were confirmed to have been reused*

- 13% were dumped or incinerated.

- 52% fell under the “unclear” category stuck in opaque supply chain where they ended up in warehouses, or unknown places, making their final fate impossible to confirm.

These results raise serious questions about transparency, waste, and environmental justice.

Online map public has been able to follow the journey for the past 11 months

CIRCULARITY IS LIMITED

Despite 22 out of 23 items being in good, reusable condition, only 6 found a second life, bringing the reuse rate to just 30%. Take back schemes and clothing banks are very quick to use the term ‘reuse’ when describing what happens to peoples unwanted clothing, However the reality is quite different.

Our investigation found that only 2 out of the 7 items reused, were brand new. The more decisive element was not the state of the clothes, but rather the composition: 5/6 were made of at least 98% natural fibres.

What that shows us is that circularity is much higher when items are of good quality (made of mono material, rather than brand new mixed composition, with polyester dominance). Quality matters. Design matters. Composition matters. Circularity won’t work without them.

A CASE OF TEXTILE OF WASTE DUMPING.

One item showed a troubling story. Although our experiment focused on investigating the fate of reusable clothes, we also used this opportunity to get data on a sample of clearly damaged item. In the original batch, 2 items were clearly not reusable. Only 1 provided usable data that can be incorporated in our end report.

However, this item, deposited in a Clothes Pods (TRL limited) travelled through the same system as the “reusable” garments. It immediately exported outside the EU from Northern Ireland without proper sorting.

Our one-legged jeans reached a local second-hand clothing market in Lomé, Togo, where the signal stopped after 2 weeks. VOICE classifies this item as dumped. This mirrors what many organisations have documented: receiving countries increasingly report shipments of unusable clothing entering under the label of “reusable,” with local marketers and municipalities left to manage the waste through open dumping, burning, or overloaded landfills. This item should never have been exported.

READ OUR REPORT

THERE ARE BETTER MODELS

The investigation also identified positive examples that could serve as templates:

Oxfam Ireland (M&S Shwopping scheme): the only example where clothing was actually reused in Ireland, thanks to local sorting and resale.

H&M & Looperstextile: 2 out of 4 tracked items were reused, and nothing was exported outside the EU into unclear chains.

These examples demonstrate real efforts, and real success, in promoting reuse, with strong transparency and quality standards in place. However, their impact has limits: once the clothes move beyond their immediate systems, that transparency can disappear, and the items may end up in the hands of actors who are not required to follow the same standards or practices.

Primark exemplifies this issue. While all items went through the Yellow Octopus facility in Poland as stated on their website. Most items (4/6), regardless of their state (new or used) where exported to the same facility in Jordan with a real unclarity over their end fate.

A SECTOR WITH NO ACCOUNTABILITY

Across the sector, VOICE found huge variation in transparency and almost no regulatory oversight. There is no requirement for collectors or exporters to report on:

Volumes of clothes collected.

How much is sorted and how.

Where items are sent and for what intended purpose (reuse, recycling, disposal)

Additionally, there are no traceability mechanisms to monitor what ultimately happens to exported clothes. This leaves Ireland with no clear picture of a trade involving thousands of tonnes of clothing each year.

A SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Public trust is collapsing: a recent EPA national survey revealed that 73% of people want assurance that their unwanted clothes do not end up in ‘clothes mountains’ abroad. This assurance does not exist in the current system dealing with the end of life of our clothing .

However, we wish to question Ireland’s textile waste crisis and responsibilities at a more systemic level. The system we investigated is first and foremost collapsing under overproduction and overconsumption, which have dramatically increased over the past two decades. There is no accountability for how much is placed on the market, how quickly it is used up, or how much is ultimately discarded either. What was once a functioning second-hand system has been overwhelmed by sheer volume, pushing more low-value items onto export channels that cannot cope.

Responsibility must therefore be shared across the entire chain: from producers and retailers to consumers, as well as reuse, recycling and waste operators. End-of-life transparency is essential, but it will not solve a crisis created at the production and consumption stages.

“There is a lack of accountability on producers, on people, and on everyone in the chain.” Mark Sweeney, Donated Goods Strategy Manager at Oxfam Ireland.

Real change requires all levels to move simultaneously by reducing the amount produced, improving what is designed and sold, supporting longer use, regulating what is exported, and ensuring traceable, accountable treatment of what becomes waste. Only a whole-system approach can build a fair, functioning textile ecosystem.

WHAT MUST CHANGE

VOICE calls for urgent political action to close these gaps:

Mandatory reporting of post-collection volumes, sorting, export and outcomes for all collectors and exporters.

An Extended Producer Responsibility scheme that prioritises reduction and reuse, sets strong eco-modulation fees, and integrates international justice into its design through a traveling fee to the end waste manager.

Investment in local, high-quality sorting, reuse and recycling infrastructure, building on current best practice in Ireland.

Explore the Clothing Tracker Map HERE

Read the final report: HERE

*During the review, a categorisation error was identified concerning the recorded end fate of one item (out of 23 analysed). The item had previously been classified as having an “unclear” fate. Upon review, its last recorded location was found to align with the criteria used in the report to define an item as “reused.”

As a result, one item has been reclassified from “unclear” to “reused,” leading to minor adjustments to two percentage figures in the findings: 30% of items have been reused (previously stated as 26%) and 52% had unclear fates (previously states as 56%)

These corrections and do not affect the overall findings, analysis, or conclusions of the report.

Watch our Fast Fashion’s Final Journey; What Really Happens After You Donate Webinar.

Ever wonder where your donated clothes end up? We uncover the truth behind the fast fashion industry. Our experts dove into the journey of donated clothing, from collection to its final destination. Get ready to be surprised by what really happens after you drop off that bag of clothes. Watch our webinar now...